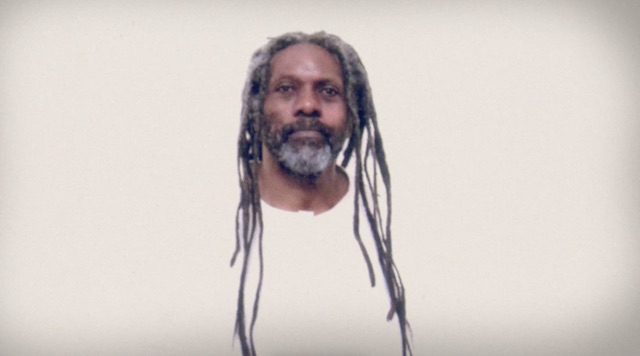

HOLLYWOOD, CA (LA ELEMENTS) 6/6/2024 –“The first thing you notice about Pelican Bay? It’s so quiet. It’s quiet. And then the loneliness man. Man, that loneliness will kill you.” – Faruq Salvant

The documentary film, The Strike, by directors JoeBill Muñoz and Lucas Guilkey, brings to light the human cost of solitary confinement in California prisons and the fight for change. This film delves deeply into the history of how California allowed Pelican Bay State Prison to weaponize solitary confinement mostly against African American and Latino inmates. Located near the Oregon border, its remote location makes visitation extremely difficult for many families. Pelican Bay State Prison is California’s highest security lock-up. In the words of Bob Ayers former warden of Pelican Bay, the prison was reserved for “the worst of the worst.”

The Strike reveals the prison’s origins with news footage of its 1989 inauguration by Governor George Deukmejian. This supermax was designed with a Security Housing Unit (SHU) for prisoners selected for solitary confinement. Each cell was about as big as a parking space and exercise was done in a small, enclosed concrete area. This design served as a model for other prisons throughout the country. Former inmate Michael Saavedra describes the SHU as, “It’s like a prison within a prison. But it’s more of an underground prison.” The quickest way to end up in the SHU for an indeterminate time that often stretched into decades was by being a gang member. This was done in the name of safety for the prison staff and the other prisoners. And what was the validation process for being identified as a gang member?

From Investigator Brian Parry we learn that if letters and drawings were analyzed and determined to be gang-related, no further investigation was needed. “Not a complicated process. We validated a lot of people. Very very quickly,” says Parry in the documentary.

Investigative reporter Shane Bauer reveals in The Strike, the role that race played in deciding who was sent to the SHU. “The evidence used to put people in solitary sort of depended on their race because prison gangs are racially based. Black prisoner who are politicized get kind of swept up. Literature about the Black Panthers or about what they call Afro-centric ideology could be evidence that a person is connected to a prison gang. For Latino prisoners, it could be Aztec history or symbolism of the United Farm Worker.”

The Strike succeeds in delivering an impact to the viewer that is powerfully emotional. There is a part in the film where several prisoners state the number of years served in solitary confinement. We learn that Michael Saavedra, almost 20, Jack Morris, over 30 years, and the list goes on and on. As a viewer you can’t help but wonder how someone would not go insane living decades without human contact. “Imagine reaching a point where your memories start to fade and you have no way of creating new ones,” says Morris.

The stress in the voices and faces of the incarcerated men make it clear that some of the despair from that time continues to linger. And yet, this film doesn’t go easy on them. We learn how a few ended up in Pelican Bay. Morris for one while in a drunken rage, stabbed a man to death. He doesn’t go easy on himself either. “Every day I say his name,” says Morris of Julian Encinas, the man he killed.

Although communication among the prisoners in the SHU was difficult, it wasn’t impossible. A shout down a drain could be heard by someone else. In time, the prisoners realized that it was up to them to do something in order for life in the SHU to change. One of the prisoners read about the hunger strike of IRA member Bobby Sands, and in January of 2011, the inmates started making plans for their own hunger strike. Some of the men in the SHU felt that not much would be accomplished even though it seemed to be a good idea.

“I didn’t think it was going to be effective because us in the SHU starving ourselves, it’s no big thing because they brought us there to get rid of us anyway.”

Faruk Salvant

Letters were sent to people on the outside asking for support. Radio Station KHSU Sister Soul had Dorothy Canales, a prisoner’s rights advocate as a frequent guest.

Although this documentary is called The Strike, it would take more than one to win meaningful concessions. The prisoners had 5 major demands including the end of indefinite solitary confinement. The first strike began on July 1, 2011 and when it ended after 20 days, only minor concessions had been won along with a promise by the Department of Corrections to take a closer look at what could be improved.

The first strike also resulted in hearings of the Pelican Bay State Prison policies in front of the California State Assembly. Assembly Representative Holly Mitchell is seen grilling Undersecretary of California prisons Scott Kernan, as to the unchecked power of the Department of Corrections. “I think that those individuals have greater power than members of the bench who are governed by decisions that we make in this body every day in terms of the length of sentences they can issue a person to be incarcerated. And yet we have this administrative-only kind of process that decides how long someone can stay in the SHU,” says Mitchell.

After the first hunger strike, human rights lawyers started to represent the men of Pelican Bay in a class action lawsuit against the state of California. Meanwhile, progress was delayed by the constant change of directors over at the Department of Corrections. This meant that suspected gang members could continue to be held for an indefinite amount of time in solitary confinement. Frustration by the inmates boiled over and on July 8, 2013, another hunger strike was called.

The second strike would be different from the first because the inmates were talking about not stopping at all this time.

Word was spread on social media through Dolores Canales.

Pelican Bay responded by separating who they thought were the organizers of this new strike. This resulted in Saavedra being transferred to Corcoran. The prisons also censored news information so the hunger strikers wouldn’t know that people on the outside were also protesting on their behalf. During this strike, demands were made to release the people who had been held in solitary for 10 years within 6 months. Both sides were at an impasse. The inmates dug in by saying that they were prepared to starve themselves to death if necessary.

Janet Mohle Botani Former Medical Executive California Prisons says in The Strike, “People can survive without eating for two months. But they will start getting severe symptoms after about one month.”

“After the first month, you don’t think about it no more,” says Saavedra. “You’re just trying to stay awake. Trying to be alive when your whole body is shutting down. Shutting down.”

“I went 36 days without eating and I lost about 40 pounds,” says Paul Redd. “I had high blood pressure. I was a diabetic, so I had to be conscious of what I was doing.”

The outrage of men starving themselves to be treated fairly in prison was undeniable. Even prisoners across the world including Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails joined in solidarity. Actor Danny Glover supported the protestors because one of his nephews was in solitary at Pelican Bay. And yet California Governor Jerry Brown remained silent as the days passed throughout the second hunger strike. However, tragedy during this strike led to pressure on the governor to do something.

For all the vast detailing of the revelations of a previously unknown prison policy, The Strike is surprisingly fast paced and will hold your attention throughout its 1 hour and 26-minute running time. This documentary is thought provoking in that it challenges the audience to question if even people who have committed the ultimate crime of taking a human life deserve some justice for themselves as well. How far exactly should punishment go? And like most compelling films, this one comes with an ending that you will never see coming.

You can see the trailer here:

I caught up with JoeBill Muñoz and Lucas Guilkey at the LALIFF screening of their documentary at the TCL Chinese Theater in Hollywood. The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Audiences love to know a little about the filmmakers themselves. Where did you go to film school? Or did you go to film school?

I did not go to film school. Lucas and I actually met at UC Berkley School of Journalism, and they have a documentary program within the journalism school that is a very great documentary program but it’s not a traditional film school.

How long did it take to make this documentary from beginning to end?

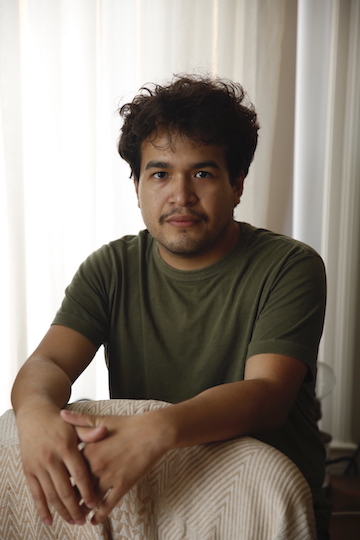

Lucas Guilkey

It was conceived of as an idea 11 years ago and then we’ve been working on it in earnest for the last five years.

So as of the last five years that’s when you were actually getting the interviews?

Lucas Guilkey

Yes

Joe Bill Muñoz

And collecting the archival materials.

Lucas Guilkey

I shot a little bit on a DSLR a decade ago and we used some of that as well.

When you interviewed the prisoners, those were face to face interviews. Is that right?

Joe Bill Muñoz

Yes. And just as a quick aside, we started connecting with them around 2019. The hunger strike happened and that got them out of solitary confinement, but a lot of them didn’t get out of prison until years later. When we started filming with them, meeting them, doing those face-to-face interviews is kind of really when the project started.

At one point in the documentary, they say that now in California solitary can only be for five years. Are officials holding to that, five years as far as you know?

Lucas Guilkey

That’s a really good question and I don’t know if I should be the expert to answer that. First, I just wanted to add, we had to simplify in the film. There were actually three hunger strikes. The first one kind of happened in two phases that we did simplify into one. So California was holding people for decades in solitary, the longest up to forty four years and as a result of the settlement after the hunger strikes, it was formally to five years. And policy wise, that is the standard. The United Nations standard is 15 days and more than that is a violation of the ban on cruel and unusual punishment. So there’s movement now amongst the protagonists of the film especially to pass the Mandela Rules to meet the U.N standards. But California does formally limit it to five years.

When doing research for this documentary what surprised you the most? I’m sure going in you probably had some pre-conceived notions but then there were probably some instances that took even you by surprise. What were those moments?

JoeBill Munoz

One of the surprising things was just how significant Pelican Bay is in understanding not just the trajectory of the prison system and solitary confinement in California, which is what the film focuses on, but it’s a marker in the national prison system. What people call the age of mass incarceration where we are today, Pelican Bay is a really important kind of marker on that timeline, on that trajectory. So, it was surprising to find the footage that we found of the opening of Pelican Bay and just how celebratory and the pageantry of this event. There was a lot of stuff. There was a pastor who blessed the prison as it opened. A color guard did a presentation. The governor who spoke at the opening says himself that this would be a model for other states to follow. So that was interesting because the film focuses so much on Pelican Bay and on California. But there’s a whole bigger story about whats happened nationwide in solitary confinement as well.

I think audiences will be shocked, I know I was, discovering through your film the length of time that people could be held in solitary confinement.

Lucas Guilkey

I think I was too. That fundamental basic detail continues to be the most shocking.

There’s a part in the documentary where Dolores Canales talks about how she was going into supermarkets and talking to random people about what being in solitary confinement is really like. She backs this up with photos. And people are stunned. They have a hard time believing her. They feel that if this kind of thing does happen it doesn’t happen in California.

JoeBill Munoz

Exactly. And it also speaks to the power of the family members because a lot of the family members went through that period of time, not fully even understanding the conditions of their loved ones, and then they’re like, ‘Oh my God. I need to educate the rest of society.’ And how active these mothers and sisters and wives and daughters became. “

At one point in the documentary before the second strike, they’re talking about some of the concessions that were going to be made. One of them is being allowed to have one phone call. Was this one phone call a year?

Lucas Guilkey

Because before that for many decades it was zero phone calls unless an immediate family member died, which was kind of its own form of abuse because if you get a call you know a loved one has died.

What drew you to this subject matter?

Lucas Guilkey

For me, I had been politicized around racism and white supremacy as a teenager and I was doing various forms of racial justice activism as a young person. And I was doing media work and I volunteered to make social media videos around what was happening because I just knew people connected. I just saw it as a really pivotal moment in California history that was still not understood enough or understood well. It’s just a pretty astounding story of a grass roots social movement right at home in my home state that I wanted more people to know about.

What do you want people to take away from your film?

JoeBill Munoz

Just how difficult it is for things to change for actual change to happen. Like, the extent to which the family members had to go through to get public attention to get public awareness to educate themselves as Lucas was saying first, but then just to educate others. And then of course the extent to which the incarcerated people themselves had to go through in terms of doing a hunger strike to call attention to this. But then you look at even the legislation, one of the branches of our government where legislative change is supposed to happen, even they sort of were struggling to get through.

We want people to understand just how the political system works and how actual effective change can happen. In this case I think one take away can be the power of collective organizing of people coming together. Diverse groups of people, the men who for years were adversaries in the prison system, came together. Not only did they come together but their families out on the streets also came together. And with that coalition were able to get something done.

Lucas Guilkey

I think there are a lot of messages, a lot of levels of this film different things that people could take away that it’s been cool to hear about and experience. One is prisons are kind of by design, made to invisibilise and disappear people from society. So, I’d like audiences to take away, which this might already be obvious to some audience members but not all, that people incarcerated in these prisons, jails and detention centers, are very much part and parcel of our society and we have a responsibility to them and these places to not forget about them but also to know that some of these horrors happening inside are our responsibility. And kind of as Joe Bill alluded to the power of collective solidarity.

Why do you think it’s taken so long on the legislative part to get anything done in regard to the prisoners?

JoeBill Munoz

That’s a very good question. I don’t know if I’m the expert on why that would be. There were legislators who educated themselves and really went to extents to understand this process. But ultimately, as the film says, what kind of tipped the scales was legal action. Sometimes that’s mightier.

The Strike screened on June 1, 2024 at the Los Angeles Latino International Film Festival.

The Strike

Directors: JoeBill Muñoz, Lucas Guilkey

Executive Producers: David Menschel, Robina Riccitiello

Producers: Joe Bill Munoz, Lucas Guilkey

Cinematography: Victor Tadashi Suarez

Editor: Daniela I. Quiroz

Original Score:

Samora Pinderhughes, Chris Pattisall

With: Jack Morris, Faruq Salvant, Paul Redd, Michael Saavedra, Jorge Ernesto Lira, Lorenzo “Dadisi” Benton, Michael Montgomery, Shane Bauer, Dolores Canales, Brian Parry